CONVERSATIONS

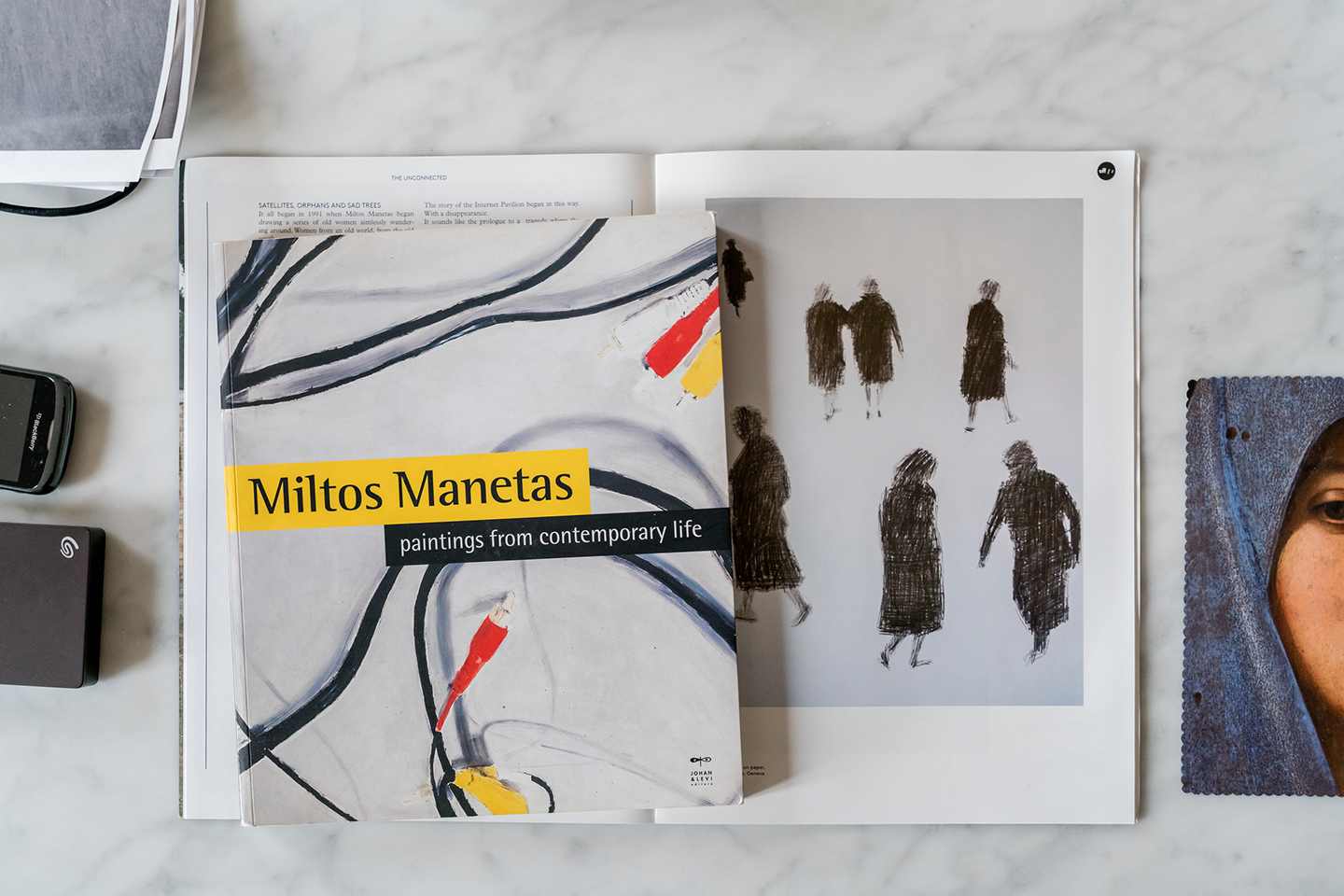

Make a Wilderness: Miltos Manetas

Miltos Manetas interviewed by Chiara Moioli

“Everyone’s updating their hardware

Plugging in their new gear

Upgrading to all-new components

Replacing the things from last year

[…]

The tools that we used to create them

They’re no longer welcome ’round here

Everyone’s re-routing their cables

Creating paths that are crystal clear”

.

—Joe Goddard, “Electric Lines,” from Electric Lines (London: Domino Recording Co. Ltd., 2017)

Miltos Manetas (b. 1964, Athens) is a charming caractère and a real go-getter. A painter, yet also a pillar in the development of what will later be dubbed Post-Internet art, with the founding of the art movement known as Neen he, among many fellow practitioners across the world, captured the zeitgeist of a generation of artists working on- and offline, blurring the boundaries between the digital and the material world, shaping the mind frame of a newborn attitude toward the notion of art in the twenty-first century that he later sorted under the umbrella of “Ñewpressionism.” His memetic mantra, “Outside of the Internet There Is No Glory,”1 is somewhat of an oxymoron that fully exemplifies the symmetry of his seamlessly distributed practice.

For MILANO, currently on view at Torre Rasini in Porta Venezia, Milan, the artist reunited his Cables paintings (1997–ongoing) portraying a “family group in an interior” in a world where technology itself has become “our” family.

In the following exchange, Manetas retraces his career starting right from his arrival in Milan, mapping his movements around the globe—each one coinciding with a new stage of his work.

“Milan is certainly not a city but a condition.”2

CHIARA MOIOLI: You surely know this town very well: this is where you lived; studied (at the Academy of Fine Arts of Brera); fell in love (with Vanessa Beecroft); and started your career as an artist (your first paintings, the Sad Tree series, were realized here, in late 1995). Let’s start from this city, after which the show is titled, and from this building, Torre Rasini—a historic tower designed in the 1930s by Emilio Lancia and Gio Ponti—in which MILANO is staged.

MILTOS MANETAS: I encountered Torre Rasini from the first days that I arrived in Milan in 1986. I had to be a student of art. When I came to Italy, I first went to Rome, following a Greek woman. There I realized that I couldn’t stay because Rome was south and there was not “the air of the north.” Now, what did I know of “the air of the north”? I was just a Greek southern guy. Later I understood that inside southern guys there is some kind of software, something that sends people from the south toward the north. I hitchhiked to Milan and met a Greek junkie, the first serious junkie of my life—I was into drugs, but I was not into heroin—who offered me [a place] to stay at his house, and I moved in immediately; there was only one record playing constantly in the apartment, The Cure—all day, The Cure. I was living with I don’t know how many Greek “architects,” who were all heavy heroin users and were selling drugs at the Giardini Pubblici di Indro Montanelli in Porta Venezia, here. I would go to the park to check out the situation, see their clients. So I was in the Giardini Pubblici, and as an ambitious young man I saw this tower, the Rasini tower, which I did not know at that time, but it has a history, and it’s the history of those years. I was in Milan, and I was a “painter.” I was wonderfully empty and living with these drug addicts, also using some drugs that emptied my brain, like ketamine.

It was a completely different Milan: it was a very gray city, full of young people in the piazzas. The next year they were not there because “Operation Europe” already had programmed that Milan would be one of Europe’s capitals and had to be cleaned; but in that moment, it was piazzas, people selling drugs, people consuming drugs.

At the Academy of Fine Arts of Brera, I encountered Luciano Fabro, who was not my professor, but I would observe him and go to all his lectures. I was ready for something which I thought would be Conceptual art, because that’s what the cool people around me were doing. Then I started going to museums here in Milan, and I was in shock: it was the first time that I actually saw paintings, “real” paintings by “real” painters: Piero della Francesca, Raffaello, Mantegna, Tiziano, Tintoretto, Veronese, people like those. I felt like I was not prepared, since I came to the arts because I found a book on Jackson Pollock and thought, “Look at that. It’s so simple. It looks easy.” That kind of art had this energy, this easiness. But in Milan I encountered another kind of painting, which became my painting. Of course, I never imagined that I could actually be part of that, because I didn’t know if I had the talent. Moreover, showing painting at the academy was not welcomed as it was a school led by Luciano Fabro, some kind of “general” of Conceptual art. There I learned my first lesson about “What is art?” Art is a wall of separation between who knows and who does not know; and those who do not know deserve all the hammering, all the bad treatment they get. And the cool artists are the ones with the hammers.

CM: How did you start painting in this context?

MM: I did not. I went into the Conceptual thing, started making some of that and finished the art school. After having graduated, Diego Esposito—my professor—said, “Okay, great. Now, you have finished the art school. Here is the number of Denys Zacharopoulos [who was curating documenta IX with Jan Hoet]—go there.” I went to Denys Zacharopoulos and got in touch with another type of artist and curator, people from an older generation, the generation after the Arte Povera. They gave me contacts, telling me that I was going to have a great career, that my work was great because everybody was doing stuff like that. A synchronized ballet of “That’s great! Everybody does that. Just continue like this.” I was in shock, and I wanted to destroy everything I did.

I was in Greece, and from a window I observed some old ladies passing with their big bags and curved bodies, walking slowly. I saw them, and they looked like satellites. I started this project, Satellites (1990), which did not fit great in terms of Conceptual art. I took at least three thousand transparencies of old women and started making drawings, which later attracted the attention of Adelina von Furstenberg, who wanted to make a show at Magasin of Grenoble, but it never happened. To close the Satellites project, I staged a photograph where seven young men appeared as “Satellites”—dressed as old ladies—at the Galleria Fac-Simile in Milan, then made a video where I was going around Milan dressed always as an old lady but in red, a “red Satellite.” My vocation was painting, but I had even forgotten that that was my vocation: I had conformed to the Milanese style. Satellites was a project of rupture—a very important one, retrospectively. I was breaking with something.

At the same time Vanessa Beecroft, my girlfriend at the time, was becoming rapidly a famous artist by displaying gorgeous-looking women in galleries, and this produced sadness in me, because my work and hers were kind of similar, but my women were completely not winning because they were old. Her artworks were beautiful, amazingly beautiful, colorful, and there was no way I could do something against her with my Satellites or with my other conceptual projects. Vanessa was doing fantastic art. You would look at it, and you would not want to stop looking at it. So where could I go? Nowhere. I decided to be a writer: bye-bye, art. I was defeated. But I had my discrete success: I had three exhibitions in museums and one solo exhibition in a gallery. One was with Nicolas Bourriaud, Traffic, at CAPC musée d’art contemporain de Bordeaux (1996), and defined what later became known as Relational aesthetics. Before closing with art, I thought: “At least I’ll try to do this one thing, this ‘painting,’ that I always liked. Can I make one of them, with oil, that actually is representative, is a representation, and it’s not abstract?” I called Vedovamazzei because I knew that Simeone [Crispino] knew how to paint; he gave me a series of instructions—which later I published on the website francescobonami.com3— and I tried my luck. I bought a projector because Simeone told me that if you don’t know how to draw, you buy one. I bought a projector and some trees used for architecture, and I made Sad Tree (1995). Inside this painting, there is me at that time, that sad tree: it seems weak, curved as if the wind is blowing; but it can come back.

All my friends in Relational aesthetics movement were super angry as it was the only painting in the show, and nobody wanted that. Nicolas Bourriaud said: “It’s not a painting. The tree makes a performance.” But it was not accepted by the others. The project that brought me to this show was a Relational aesthetics project, which involved a computer that the museum had bought for me, Tiramolla.

The Tiramolla, a character from a cartoon of the 1950s, was an elastic man that could assume any kind of form. The Tiramolla was a “communist cartoon” because it criticized the “society of the spectacle.” He was actually a privileged guy who lived in a beautiful house; he was a nice guy: a metaphor for the bourgeois world. Through this character, the writer, who was a Marxist, I suppose, uncovered things that were hidden in society. He did not tell you the straight truth, but he led you into understanding. With that project, there was this Tiramolla connecting himself with a computer; when he did that, I connected myself to the wall: we put there a computer, the computer did something, and I did something to react. I had the reputation of the guy who worked with computers in this relational way. With that project all the people of the Relational aesthetics field were all happy. By showing the Tiramolla, they got their piece; and I got my piece with the Sad Tree.

To my disconcertment, people from the art world were interested in the paintings—so what to paint? For me, painting needs only one thing, a subject. Without a subject, you are not a painter. So I was in trouble.

CM: This is the point when you turned to Vanessa, asking, “What shall I paint?”

MM: Vanessa was reading Andy Warhol to actually see how she should behave, because at that moment she was going up to the Andy Warhol level. She was like, “I don’t know. But here it says Warhol had the same problem, ‘What shall I print?’ and a friend of his said, ‘Andy, what do you like the most?’ And Warhol said, ‘Money.’ And that friend said, ‘So, print money.’” And Warhol printed money. Thus when Vanessa asked, “What do you like the most?” I asked myself: “What do I love the most?”

CM: Love or like?

MM: Love, love, love. What do you love the most? It is love, not like. Where is your heart? And I said, “My laptop.” So, “Okay, I’m going to paint my laptop.” I still didn’t have the confidence to paint. So I painted a laptop, but closed, because after all it was just a monochrome.

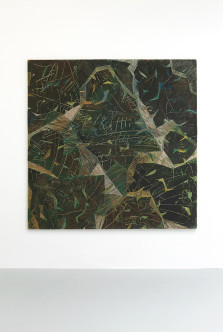

CM: These paintings come from your series New Abstraction (1996–ongoing), one of which—PowerBook (Apple laptop) (1997)—is included in MILANO. These kind of works can be inscribed within a well-established tradition in modern painting, that of the representation of people in their modern settings—to recall Charles Baudelaire’s The Painter of Modern Life (1863). What turned you toward depicting technologies in the first place?

MM: The subject. It was available: nobody had painted computers, or at least, I had never seen a computer painted on a canvas. My intention was to paint one of them and finish it. But once I made it, I realized that the Consortium of Dijon, which asked me to do a show there, SELECTED OBJECTS (1986), was quite big. I had to do something else. I started having courage. So I painted the computer semiclosed, turned toward the wall; I painted the computer open, facing us; I added objects, starting from QuickTake, Apple’s first digital camera. I was learning and trying my luck. And then this beautiful exhibition came out. In those paintings, I tried to collate the information I had gathered from my museums visits, so, for instance, they included the proportions of Tintoretto, the colors of Veronese. I went around asking: “Have you ever seen a computer painting?” “No.” Nobody painted screens. Nobody painted computers. Bingo: there you have it.

These paintings were made in New York, but this process was actually taken from Milan and transplanted in New York; for me New York was just Milan. It was north, just a continuation of the north. With these paintings I got success, and Milan opened. Once you are an insider, all the doors open. This is the north. You enter what Toni Negri calls “the Empire.” You enter into that place that is all around the world, where everything is privilege. Every European is privileged in a relationship with the world, but then it starts a chain of privilege plus, privilege plus plus, privilege plus plus plus, and goes up to some degree where there is no privilege anymore, because it’s like so full of privilege that what is your privilege? It’s just competition of charities. People said I left Milan. I never left Milan. I just moved. I went to New York, which is Milan.

Wireless came along, but the cables remained…4

CM: Your Cables canvases are the core of the show; you started painting them in New York in 1997 and, for the first time, this production is reunited under the same roof, while new “members” of the “family,” as you labeled this series, are currently being created during your stay. Can you talk about how this series came to be and what it represents to you now?

MM: The Cables were a coronation of that new series of paintings, because cables are what you see next to a computer. With the cables, I was in the clouds. I was happy. Finally, I could be what I thought I always wanted to be: a master. I could go on forever.

But something subconscious later sent me away from there. From 1998 to 2008, I was doing research, of all kinds, new things moving in all directions; I relocated to Colombia and immersed myself into a whole nother landscape which later included social kinds of things; I went back to Relational aesthetics but for real this time and not for speculation, to actually give, not to get, which is very different.

Even if I know that the market is asking and people are telling me “Miltos, just do this. Just do cables. They’re so great,” I’m like, “No, no,” without a real “No,” right? For me, art was only painting: These big square things with paint on them, made with a technique that didn’t introduce anything new, just the subject. This for me is art. In fact, I don’t have a great admiration for art. I’m deeply in love, but… It’s like being in love with a bad girl. I believe that this kind of art is a woman that is a mercenary. Painting is a mercenary.

A few months ago, I was in Milan, and my Cables paintings, for some reason, were around here, after they had been all around Europe—scattered between garages, unknown places, almost stolen. I’m like, “Who would want to see an exhibition of the painter of the cables? Nothing more, just the cables, just the painter.” That’s how MILANO came about. I re-encountered the painter, a bit cynically, because I reconnected with my inner fascist here, fascist with no capital letter, with the guy who just speculates, who makes something that is privileged: this painting here is two meters by three. How many people have a place for that? And it costs money that others would use to buy a house for a family. For me this is fascist. This is like the poster picture of fascism, this kind of art, this kind of size, this kind of thing. That’s how I feel. When I came back to Milan, I returned with the voice of somebody who wants to be against it, but actually the moment I was here, I was totally comfortable with it. This kind of painting is produced from a state of comfortableness, knowing and trying to forget—and succeeding in forgetting—that vulnerable people may be annihilated by your associates or by their associates or by the consequences of things you (or they) are doing together. Anyway, now here I am in this context, and I think of these two directions. From one, I read the politics of it, and from the other, I explore the metaphysical connotation of the cable. What is the cable, after all? Recently I thought that the cable is the real Jesus because in the new religion of the digital, cables are important for the connection, for the “salvation.” But when they gave us the cables, they told us they’ll soon disappear—the opposite of Jesus, who is supposed to come back at any moment. But cables never disappeared because digital—in contrast with the story of the Gospels—is for real. For the first time, we have a religion that’s not based on the usual manipulative crap of fantasy but is based on real data. The existence of cables in our floors is an incredibly assuring thing: we can actually keep it real. They are real. They are there. I perceive a kind of reality in the cables, which can become abstraction in the paintings; still, it gives you a measure of real life. But maybe it’s just the excuse of the “fascist,” right? To have one leg here and one leg there and actually switch between both worlds.

Smells Like Neen Spirit

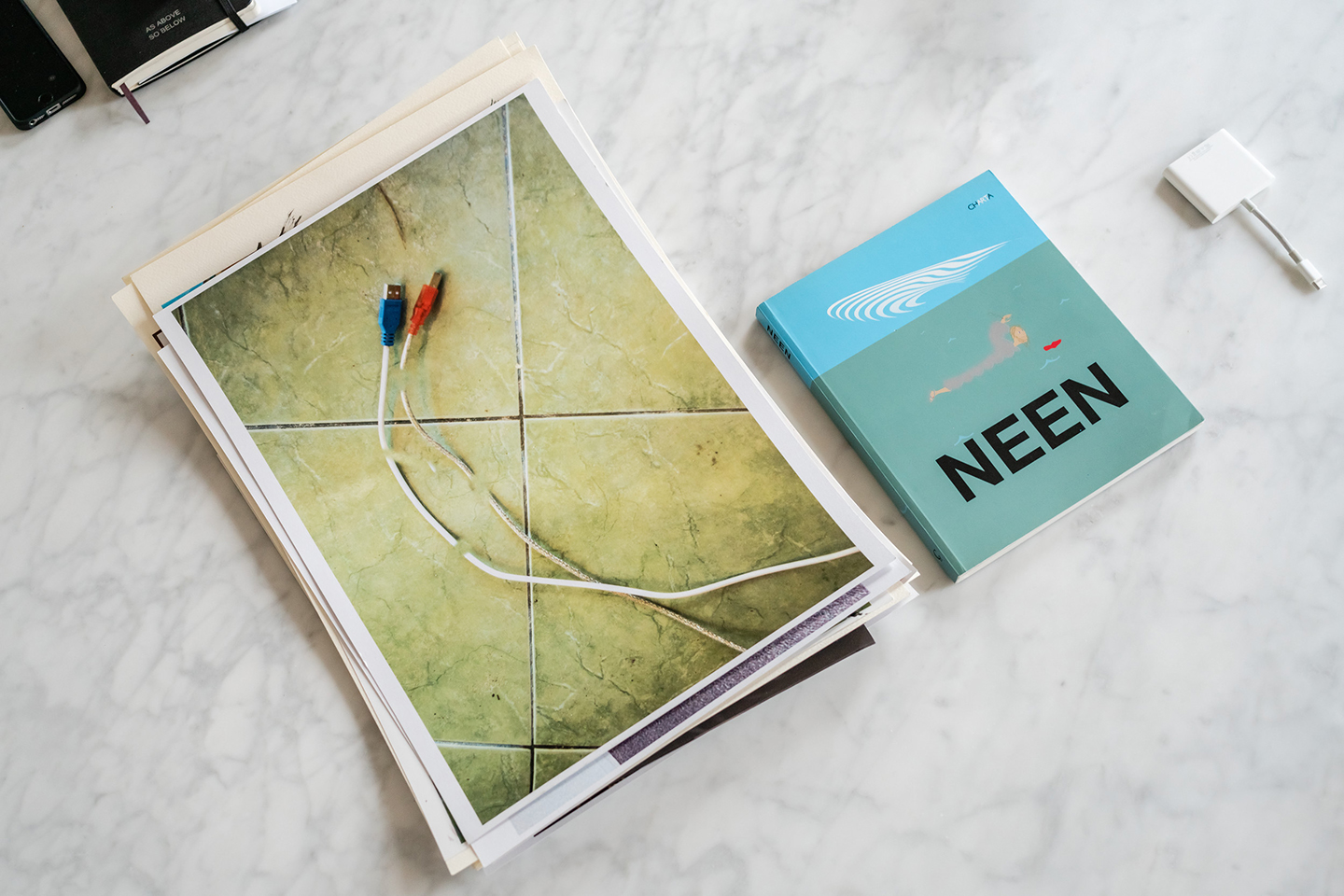

CM: Milan was also crucial for the history of Neen, with several shows dedicated to the movement and its advocates.5 Almost twenty years have passed since its founding act at Gagosian Gallery on May 31, 2000.6 To introduce the discourse, could you elaborate briefly on what Neen is, how it came about, and what its aim was?

MM: What is Neen? I don’t know. My definition of Neen is something that we agree is Neen when we see it but we can’t explain why. We’re like “Neen! Neen!” That’s it.

To expand a bit: First of all, I did not make Neen. I encountered it. My intention was exactly the intention of the painter. What I wanted was to actually see a new landscape and to represent it. I painted the computers, I painted cables. Then I saw all these things on the screen, and I was sure that those screen things would translate somehow into these—into paintings—but how would they? So I thought: “Why don’t we do a new art movement?” The idea for a new art movement was in me since the exhibition Traffic, curated by Nicolas Bourriaud, when he coined the term “Relational aesthetic,” which I thought did not sound cool but sounded more like a scientists’ thing. So I asked some of my pals to get a name. I wanted a name that was fresh, like Dada. All these people—I was trusting their brains, but no one came up with a proper name. Nobody even considered it, because it was my need only. I was a painter dropping his old subject; now I wanted to paint the Internet.

I was on an airplane reading a magazine, and I saw that there was a company in California called Lexicon that made names, the names of all of my art: PowerBook, QuickPlay, QuickTime, everything, you name it—even BlackBerry, later. This company was called Lexicon, “dictionary” in Greek. Except it cost $100,000 to get a name from them. But I was complaining to the right person, as Yvonne Force, a great producer who had worked on Vanessa’s first performances at the Guggenheim and on other wonderful things, was sitting next to me. And she found the money. We hired Lexicon, organized a meeting—Yvonne and I went there both dressed in white, in these white suits by Helmut Lang they used to sell discounted at Century 21. And we presented what later would be labeled Neen. I gave a talk, I had slides with all the Relational aesthetic stuff and contemporary art. I told them, “Look and look and look. I don’t want nothing to do with that at all, zero. Nothing, nothing, nothing. Nothing of that, okay, guys? Now look at this.” I showed them [the work of] Lucio Fontana, which they had never seen, and I told them the word “screen” and talked about the landscape of the computer screen. All of this was happening inside a wooden antique luxury boat docked in the waters of Sausalito, California, as the office of this place, Lexicon, was a yacht and their workplace a bar.

Three months later came a fax, and they had found all these fantastic names. There was one in particular that was really powerful, Telic, which I liked. But my Japanese girlfriend at the time, Mai Ueda, went, like, “I want to be Neen. I like this Neen, Neen! I want to be a Neenstar.” I was like, “Okay, that’s it. We’ll take Neen.” We had a moment of drama as Yvonne and everybody wanted Telic because it was serious and suggested technology. The Americans were embarrassed; they could not even pronounce it, Neen. It sounded as if you were hearing something annoying. I was happy, because Mai Ueda was, more than my girlfriend, my landscape; she embodied what young people were after.

Anyway, we had a name, and we did this presentation at Gagosian Gallery in New York where everybody freaked out completely. We went to Gagosian, and there were some paintings of Andy Warhol, shadows in black-and-white. I felt incredibly related to these shadows. From there it started a magic where the computers practically took existence between us. Neen came. The database started to materialize, already with those Andy Warhol paintings. They depicted the shadow of a desk; it felt as if that was exactly the moment before Neen: if there is this desk, there is a computer they want to put on it, and they’re going to start working. People came, holding a printed invitation, which was as big as a keyboard of those days and said “A new name for art.” Yvonne called the best linguist in the universe, Steven Pinker; also present were J. C. Herz, David Placek, and Peter Lunenfeld. I invited Joseph Kosuth, who sent us a paper with a video—the tape was later stolen, and to this day, I still don’t know what Kosuth said as I was not paying attention. Everybody had five minutes to talk. Sony promised to send us one of its representatives to present Neen. But in the end they did not send anybody. So I “hired” a friend of Mai Ueda, bought him a suit, and included him as “Sushi Matsuda, the representative of Sony.” I told him to not speak English: “Just do the Japanese.”

The presentation started with Pinker saying “This word, which now you will hear about, will never have success. It is a word destined to fail.” It was because the word evoked things like nina, nana—all the embarrassing kind of things in English.

I presented things that could be Neen—they were not exactly Neen, but could be. All these materials were presented on a screen. Gagosian hired the best projectionists in New York, who had worked from day to night preparing everything… And the projection came out greenish. The whole projection was lime green. All wrong. Everybody was embarrassed. Me? I was incredibly happy. That was Neen. The computer was fucking up something. That was a very weird evening. There was nervousness.

To add another level of discomfort, Gagosian told me that I could have all the alcohol that we wanted, but I specifically required Evian water only. People were so pissed off: they wanted to drink something, and there was nothing to drink. Plus they were still expecting to know the great name of this new art movement. So I said to Sushi Matsuda, “Mr. Matsuda, please press the button.” He pressed the button, and a Sony computer said, “Ladies and gentlemen, the new name for contemporary art is Neen, N-E-E-N. I hope that you like it. Have a nice evening.”

People were mad. Many, including several artists, went around Mr. Matsuda to try to close deals with Sony, but he was not allowed to speak. Fantastic event.

At Gagosian I had encountered Neen and realized that actually it was not just a landscape, it was like a spirit: a new kind of spirit going around into the world. And what was it? An informatic creature, like we are. It would produce little accidents. It would enact things that were not predicted. I was not breeding a cultural meme, I was trying to breed an essence of something. So I didn’t care for the success, I cared for existence. It was not memetic. Pinker was right, Neen did not make it because its failure was already included in the name. In a dinner later, Mai Ueda, who usually would have never said something “cultural,” turned to Pinker and said, “Steven, you are wrong because Neen—in Japan, ‘N’ and ‘E’ are a very important combination: Sony… Nintendo…” Still he was right because people, when they would say “Neen,” would smile. That smile was important because it guaranteed that it would not attract the type of unsmiling people, but it would get only a few selected ones.

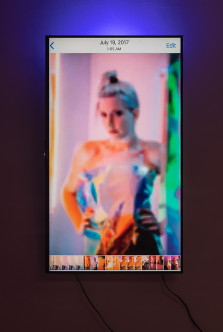

I didn’t know how to start Neen and what to do with Neen or how to make it happen. I went to Los Angeles, where I was already living, rented a space in Chinatown, and named it electronicOrphanage. My idea was to just put in a workstation with a computer and find people who were interested in computing who would come and maybe find some Neen. We parked a sofa outside of the electronicOrphanage; Mai Ueda and I stayed inside waiting to see what would happen. The first guy who came was Mike Calvert, who was an artist making videos; we made him an offer to stay at the eO browsing, computing, playing video games, for eight dollars per hour on the condition of getting rid of all his works; he agreed, and we went to the river and threw them all away. He spent the next three, four months looking, and then he came up with a computer desktop, Evian Desktop Pattern (2001):7 it was made with the mountains’ pattern from the Evian bottle’s label, but he removed the logo and projected it. Mai and I were like “Neen, Neen!” Because this was Neen. At that time we were drinking Evian, and the desktop pattern was the most important thing for us. Those were the early computer days. We told Mike he was a Neenstar and a neenster and got him a big exhibition, there, like that. We kept this show open for two months. Then Mike made an animation that was called Strawberries and Pizza (2001):8 second main artwork, another two months of exhibition.

After Mike we found a boy, eighteen years old, who was doing weird animations: Rafaël Rozendaal. We bought him a ticket to come to Los Angeles (he was from Amsterdam). He was studying design, but he was flirting with it. However, for us, Rozendaal was definitely a Neenstar. He made his first exhibition at the eO with this work, which was the most embarrassing work in the universe: it’s called misternicehands.com (2001).9 This was extremely Neen, too Neen even for me.

With Rafaël, suddenly a number of people came. They fell from the sky, a small number of incredible Neenstars and neensters: Andreas Angelidakis, Angelo Plessas. I commissioned from Andreas the Neen World in Second Life, and he made studios for all of the Neenstars based on their aesthetics. In a year and a half, we made a lot of amazing things. There was AFTERNEEN, the first Neen exhibition in CASCO, a place in Holland, where we showed the Neen World by Angelidakis. The day after the opening, a computerized car that was parking outside broke through the storefront of CASCO and destroyed the computers, everything. The first Neen show disappeared because of a computerized car. Those days, because it was costing a lot to host these Worlds on servers, we decided to host them on the computers, so we lost the whole Neen World. The gallery called me, and I was in heaven: “Yeah, that’s it. That’s Neen. Neen accident, Neen thing.” There was a series of Neen calamities where the computer rebelled as Neen did not want to be captured. This was the first, and for me the last show, even though many other great exhibitions were made; but for me, that was the end of Neen.

CM: Self-proclaimed “the first art movement of the twenty-first century,”10 Neen situated itself among early Net Art (the mythological “net.art with a dot in the middle”11—also acknowledged as “the last avant-garde of the twentieth century”);12 the Surf Clubs era; and the Post-Internet generation to come.13 What was your relationship with the Net Art scene when you developed the concept of Neen?

MM: When I developed the concept of Neen, I was immediately accused of being the posh artist who just wanted to profit from computers, and I was completely clueless about what was happening in the Internet art scene. They were absolutely right, these accusations. These net.art people were right: I had no idea what Internet art was. I had seen some Internet art, but it did not attract my interest because it did not look to me like it was glossy, glamorous, sparkling, moving around.

CM: None of it was. Early net.art was the opposite of glamour.

MM: For those reasons, I have never watched it. Since the beginning of Neen, the spirit of Neen captured me, took me from the inside. I started to become expert in computer art, having an interest in that, and admiring some of those artists a little later—also because in the beginning, there was a kind of “war” because of what happened with the Whitney Biennial in 2002.

CM: Can you retrace the 2002 Whitney Biennial “quarrel”?

MM: The Whitney Biennial 2002 had a very strong Net Art section curated by Christiane Paul. I did not know that, and I did not care about that. What happened is that I realized that the domain whitneybiennial.com was not taken. So I registered it, and I wanted to do a little exhibition on the Internet by putting whitneybiennial.com14 online. To do my online show, I started calling some curators to propose some digital artists. But I also wrote to Lawrence Rinder, the curator of the Whitney Biennial, and he said, “Wow, what an interesting idea, Miltos. I cannot participate because it’s something against my exhibition.” My little exhibition was not supposed to offend Christiane Paul or the digital artists; it was supposed to offend the Whitney in terms like: “It’s 2002, guys. Where is the Internet?” I had not even noticed that actually the Internet was there; I still did not see that as “art on the Internet.” I was expecting that the Whitney would open its doors to people like the ones I found at the electronicOrphanage, artists like Rafaël Rozendaal; for me that was valid art, or at least it had the value of an artistic thing to be shown at the Whitney Biennial. Why wasn’t that there?

Lawrence Rinder invited me to New York to talk. I went and I printed stickers, whitneybiennial.com. I went there for fun, I just wanted to tease the guy. I put the stickers on his table, and he was excited: “Wow, you want to do this?” I say, “Yeah.” “No,” he says. “Look. Look outside of the window. There is an empty Chase bank. Why don’t you bring your artists there with the computers and they do this?” I’m like, “Larry, I’m not going do that. You are here at the museum, and you have all the glamour, and we’re not going to be there in front of that like losers, like alternatives.” And then I had an idea on the step. “You know what, Larry? I’m making a lot of money from my paintings. I’m going to hire U-Haul trucks, and I’m going to surround your museum the day of the opening. I’m going to put projectors in the U-Haul trucks, and I’m going to project the Flash animation websites. So the Internet will surround you guys.” He said, “Okay, oh wow. Really, you wanna to do this?” “Nah, it’s just bullshit.”

I went home, and I started to receive phone calls from people telling me, “Don’t do that.” I was like, “I’m not doing anything. Are you crazy? I’m not doing that!” Friends started calling. The New York Times called: “We know you are doing this U-Haul trucks thing.” I replied, “I’m not doing this, but if you, the press, think I’m doing it, maybe I’m doing it. I tell you that I am not doing it, but if you think I’m doing it, I’m going to give you an interview on the possibility of doing it.” I gave them an interview but encoded, sounding like “The whitneybiennial.com that will surround the museum is dedicated to Gino De Dominicis, who was famous for his invisible art.” So I gave them all the clues to understand that those U-Haul trucks won’t be visible because they were nonexistent. The New York Times came out with a page on it: “The U-Haul trucks of the Internet will surround the museum.”

In the meantime, my little exhibition had grown to 125 works to be shown on whitneybiennial.com, on the Internet. With Andreas and Angelo, we made a beautiful website. All the artists were super excited thinking they were going to be in the Whitney. Me, I am like, “Oh, you mean whitneybiennial.com…,” and I realized the mess the whole thing had created. I did not know what to say to these people. To fix the situation, I reserved tables at Bungalow Eight—New York’s most “happening” club back then—and organized an after-party thinking that, if any of the Internet artists would actually come to the opening, they could come to the after-party. But I didn’t think anyone would show up at the opening, because they were not invited. I went to the opening with my invitation and my girlfriend; we were both dressed wonderfully. And fuck, there were like a hundred Internet people with their families asking, “When will U-Haul trucks start coming?” I’m like, “Here is the invitation for the after-party. Come!” Then I go inside the museum. Inside the museum, the art people were saying things like, “Oh, it wasn’t good. It’s bullshit, the U-Haul trucks. I’ve seen them. They’re nothing.” People inside the Whitney were saying that actually the U-Haul trucks were bullshit but were there for real. People made up things.

Of course I told the truth to the Internet artists. Many went away very unhappy, hating me, thinking I had used them. But I had not used these people, as they were the exhibition. It was happening. It was invisible, but the Internet people were surrounding the art world. Some of them I was able to bring inside the Whitney.

This accident kind of destroyed my reputation when it comes to being an Internet artist. It was very tense. Le Monde, El Pais, they published that the U-Haul trucks were actually there because they were just copying what the New York Times had published.

It was a big misunderstanding. I don’t know how these artists feel about me now. My respect for them increased because later I started looking at their works and found interesting things, but this kind of art still does not interest me if not in a conceptual way.

CM: Do you think the neensters’ attitude toward the Internet has had an influence over a whole new generation of younger artists labeled Post-Internet?15

MM: When Post-Internet came, it reinvented the wheel. I don’t say this in a pejorative way. That’s how it works, it’s civilization. But Post-Internet is not Neen. When Jon Rafman made his project 9-eyes (ongoing),16 it was related to Neen but it was not Neen. He reinvented the wheel somehow because again he gave voice to the database, let it talk. And he used himself as a program: instead of using Google, Jon Rafman was the program.

I enlarged the definition of this kind of art with the term “Ñewpressionism,”17 which to me is the big adventure of our days into the digital. Ñewpressionism is not an art movement, it’s an art tendency, an art theory. What we have all done there, including Net Art, including Neen, including Post-Internet, is a new kind of Impressionism. A new kind of expression. We are in this landscape and we paint it.

Outside of the Internet There Is No Glory…

or There Is Some, After All?

CM: Your best-known statement, “Outside of the Internet There Is No Glory,”18 is somewhat of an oxymoron but also a memetic mantra. Can you expand on this?

MM: This thing came out of my mouth like that. There was this auction in Rome with artists living and working in London (Auction In A Suitcase, 1:1 Projects, Rome), and they asked me for an artwork, and I said: “‘outsideoftheinternetthereisnoglory.com.’19 This is my work. Please register it.” And they did.

With Neen I have bought a series of websites without having a clear idea why. Mostly because they were available, and, in this case, guydebord.com20 was available. I bought it, but I never managed to actually read Guy Debord. Still I thought that there were some things that Guy Debord would say if he were alive. I attributed this statement, “Outside of the Internet There Is No Glory,”to Guy Debord in 2009. The website also says “No-internet artists are just freelance employees of other employees, the curators of the exhibitions.” It’s something that Guy Debord would say going against these artists, and it was a polemic thing against the curators. It was made for that auction, but then it started having its own life; people loved it, and it seems to survive. I believe all these things don’t arise from me; they develop from the network.

This is another element of Neen. It’s the first movement, or the first conscious one, that tells you that we are no longer the center of the universe as creators because the database is now the center. The database is the artist, so in that sense, “Outside of the Internet There Is No Glory,”which also conflicts with our basic human needs, because actually outside of the Internet there is a lot of glory, and my actual life is about that. I’m a guy who goes to the Amazon forest, goes to Sabina, in Lazio, looks at the trees. “Outside of the Internet There Is No Glory” is intended as the glory of creativity.

[1] Miltos Manetas, “Websites Are the Art of Our Times,” 2002–4. See http://www.manetas.com/txt/websitesare.htm.

[2] Miltos Manetas, MILANO, press release for the show, March 21–April 20, 2019.

[3] See http://francescobonami.com.

[4] Miltos Manetas, MILANO, press release for the show.

[5] Among the most relevant: Superneen at Galleria Pack, Milan, March 7–April 22, 2006; and Miltos Manetas, The Pirate Paintings, December 3, 2009–February 12, 2010; Angelo Plessas, Every website is a monument, January 14–March 10, 2011; Andreas Angelidakis, Travess Smalley, and Priscilla Tea, Metascreen, March 31–May 18, 2011; Rafaël Rozendaal, To Walk the Night, May 26–July 25, 2011; Andreas Angelidakis, Domesticated Mountain, April 19–May 28, 2012; all presented at Gloria Maria Gallery, Milan.

[6] See Miltos Manetas, ed., Neen (Venice: Charta, 2006), 14–23.

[7] See http://electronicorphanage.com/collection/evian/full/.

[8] See https://www.facebook.com/afterneen/photos/a.10155358044729522/10155364428709522/?type=3&theater.

[9] See http://www.misternicehands.com.

[10] See http://neen.org.

[11] See Josephine Bosma, “Different Contexts, Different Meanings,” in Nettitudes: Let’s Talk Net Art (Rotterdam: nai010 publishers, Institute of Networked Cultures, 2011), 147–149. The “dot” was later exhibited as a small golden marble ball on a red velvet pillow by net.art pioneer Olia Lialina as part of Written in Stone, a net.art archeology, the Oslo Museum of Contemporary Art, March 23–May 25, 2003. See http://www.perplatou.net/net.art/index3.htm; http://art.teleportacia.org/observation/oslo/oslo.html; http://www.liveart.org/motherboard/articles/03_netart_bosma.html.

[12] Natalie Bookchin and Alexei Shulgin, Introduction to net.art (1994–1999), March–April 1999. See http://archive.rhizome.org/artbase/48530/index.html.

[13] Andreas Angelidakis: “A lot of the stuff that later on was dubbed Post-Internet, maybe Neen could be the archeological version of that. The ancient history of that.” See https://anthology.rhizome.org/neen.

[14] See http://whitneybiennial.com.

[15] “Most Neensters would love to have their art on display in galleries and the like, but they enjoy the freedoms that the internet allows.” See http://neen.org/history/.

[16] See http://9-eyes.com.

[17] See http://ñewpressionism.com.

[18] Miltos Manetas, “Websites Are the Art of Our Times.”

[19] See http://outsideoftheinternetthereisnoglory.com.

[20] See http://guydebord.com.

Miltos Manetas is a Greek-born artist. He first moved to Italy, then to the United States, and from there to Paris and London. In 2010 he discovered Colombia. These days he lives between Bogotá and Sabina, Lazio, Italy. Bartolomeo Pietromarchi, MAXXI’s director, invited him to put together his first major museum show, Internet Paintings (Rome, 2018), a portrait of the Internet in ever expanding progress. Manetas is a painter, a conceptual artist, and a theorist whose work explores the representation and the aesthetics of the information society. He is the founder of Neen, a pioneer of art after videogames, an instigator of Post-Internet art, and a theorist of Ñewpressionism.

“MILANO” at Torre Rasini, Milan

until 20 April (by appointment only)

Curated by Francesco Maria Gloria Urbano Ragazzi Antonelli Cappelletti, in collaboration with Galleria Valentina Bonomo, Rome.